Did you know that in French, a “hotel” isn’t always a place where you can book a room for a night? A hôtel-Dieu, for example, was originally a hospital for the poor run by the Catholic Church, Dieu being the French word for God. The most famous of all these hospitals is also the oldest in Paris, created in the year 651 by the Parisian Bishop Saint Landry. Today you can find the hospital building right next to Notre Dame on Cité Island.

A hôtel particulier is no more a hotel than a hôtel-Dieu, but a grand townhouse or mansion. Their main characteristic is that they will be free-standing, most often located between the main courtyard and the garden, and of course, be in a city.

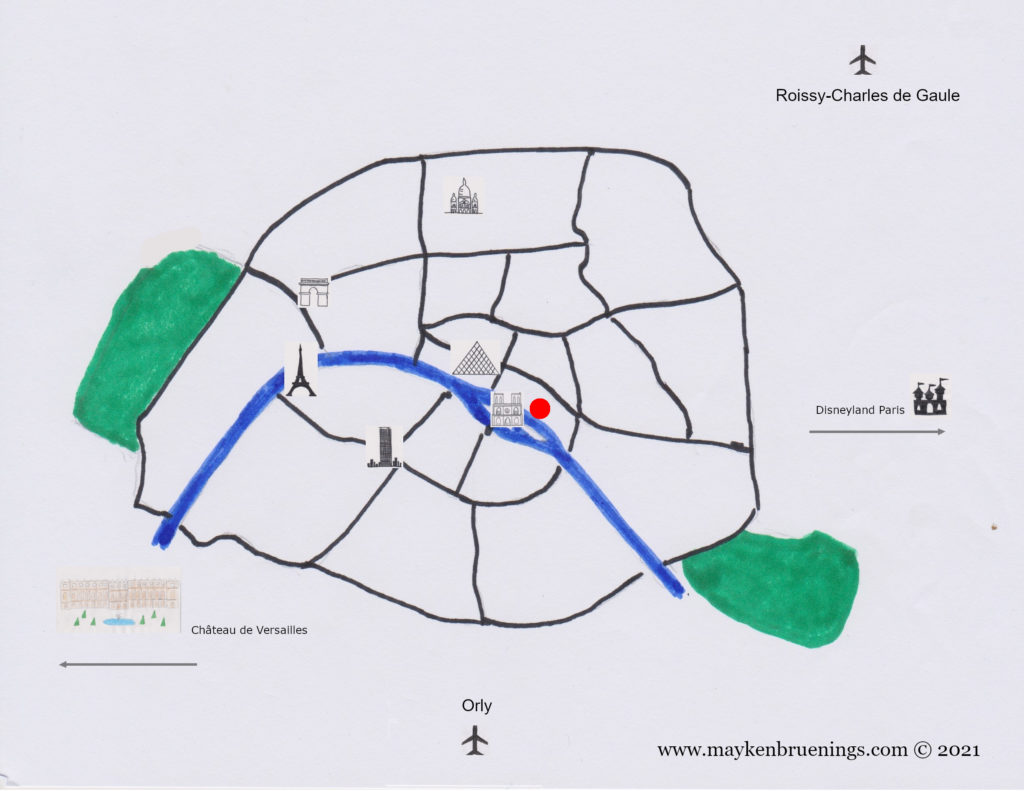

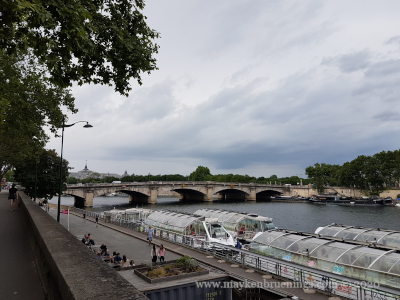

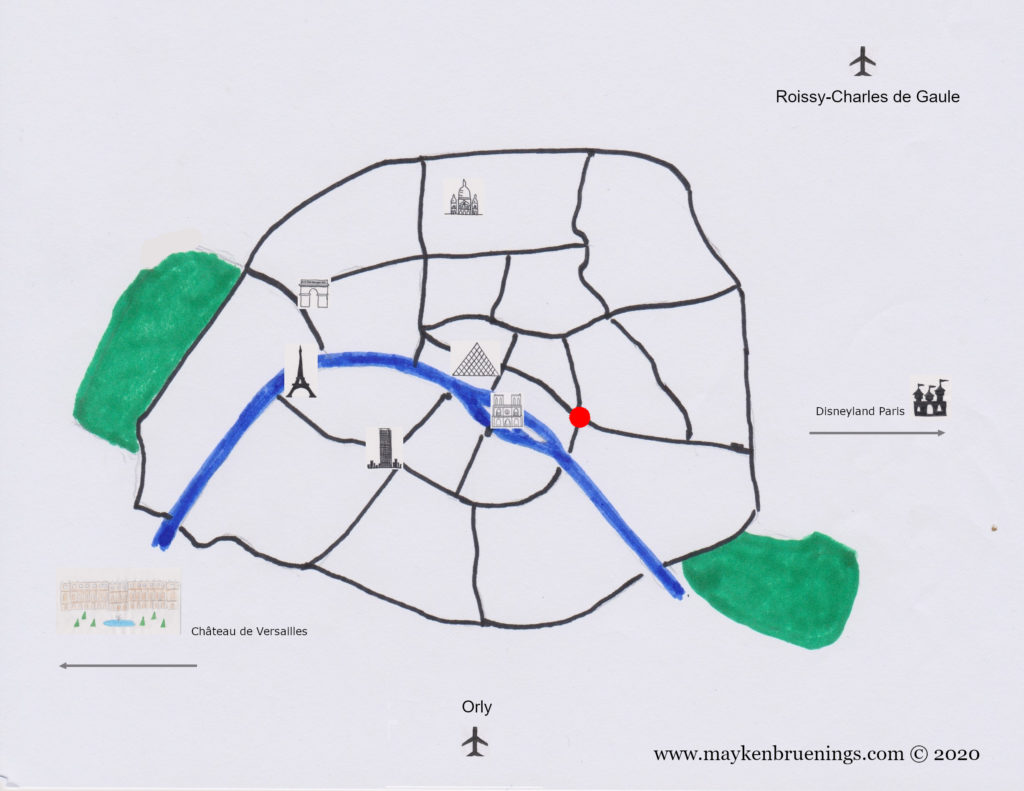

The Hôtel de Sens is a hôtel particulier built in the 15th century in the 4th arrondissement, near the Seine river. At the time, Paris did not have its own archbishop but belonged to the archbishopric of the Archbishop of Sens, a town 100km to the southeast of Paris. The archbishop had this hôtel particulier built as his pied-à-terre when he was in Paris.

Several archbishops resided there, in fact, over time, as well as other notable figures such as Antoine du Prat, chancellor and prime minister under King François 1er, Louis de Bourbon-Vendôme, a prince from the royal family, or Louis de Guise, Cardinal of Lorraine.

One resident, however, had a more eventful stay than the others: Marguerite de Valois, better known as La Reine Margot (granddaughter of François 1er and first wife of King Henri IV). Her marriage with King Henri IV was annulled in 1599. She lived at the Hôtel de Sens from 1605 to 1606. Legend has it that she had a fig tree at the door cut down because it was in the way of her carriages. Whether it is true or not, the street now bears its name.

Marguerite had a number of lovers. According to another legend, two of them fought it out just below her window. One was killed, the other executed in the same spot.

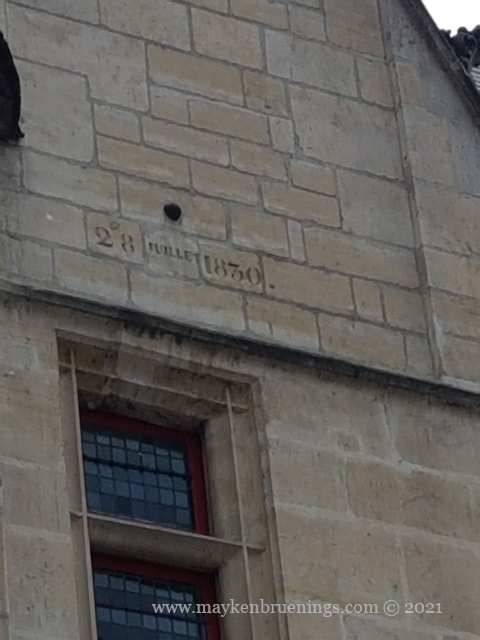

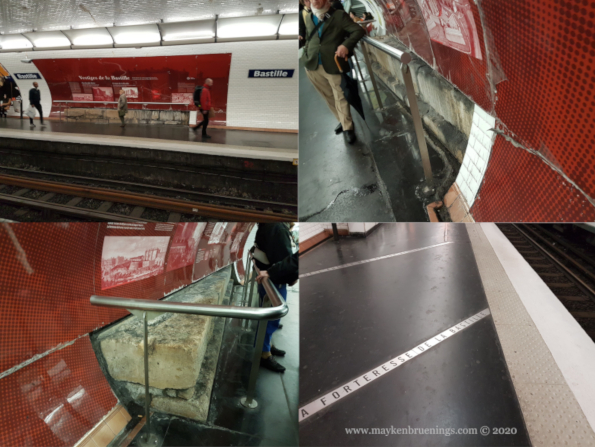

During the Revolution, the Hôtel de Sens became property of the state, was sold and housed, like many hôtels particuliers in the area at the time, shops, workshops, or factories. During the 1830 Revolution (commemorated by the July Column at Bastille), a cannonball hit the façade and lodged so deep within the wall it became impossible to remove. It is still there today, visible to any passersby, with the date engraved beneath.