Chances are, unless you’re writing historical fiction (and maybe even then), you’ll need to name lots of characters. Let me share some tips:

If you are writing real-world fiction, consider what realistic names are/were in your chosen time and place. Even if you give your protagonist a “special” name, unless it’s a main feature of your story, most named characters shouldn’t have “special” names. For research, try “baby names popular in year X” (with X being the year of your story minus the age of the character you’re naming, obviously).

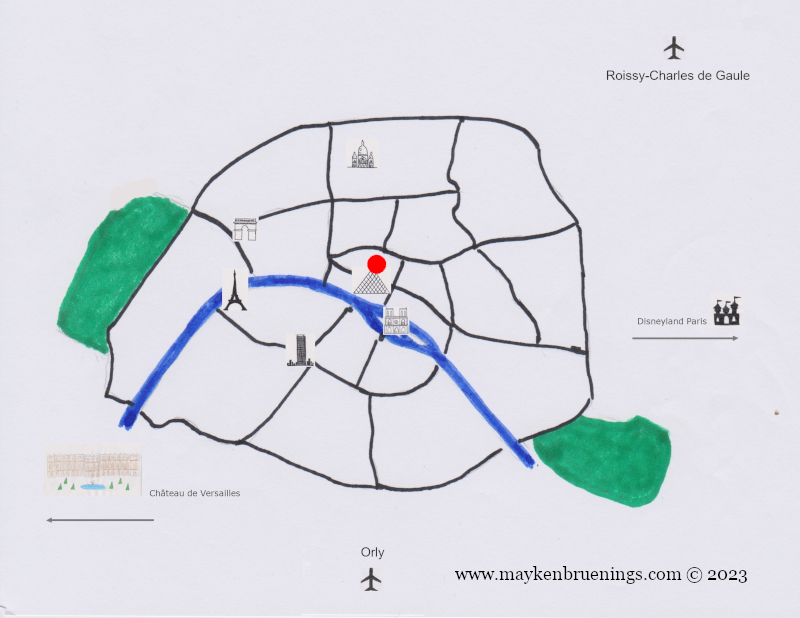

For foreign settings, try to find someone from that country/area to confirm your choices (I assure you there are not as many Pierre Dupont in France as you might think, or Hans Meier in Germany). That is especially true with names from cultures where naming rules are different from what you are used to (Chinese names are a prime example).

For stories set in certain time periods or communities, learn about naming customs. Ancient Rome had rather straightforward naming rules that can easily be reproduced and applied to fictional characters. Closer to home, in my grandma’s region of Eastern Frisia, children would receive the same names over and over again from generation to generation, and if in those big families a child died, the next one born would get that child’s name. (Much to genealogists’ despair, I’m sure.)

In a fantasy or sci-fi world, it is you who make the rules, and this includes naming. However, even there it is a good idea to remember to keep your names pronounceable. When I was reading the Never-Ending Story for the first time as a kid (when it was first released and before any movie adaptation), I struggled with the pronunciation of all the names of people and places, it annoyed me to no end. As editor Heather Alexander said at a writers’ conference I attended a few years ago, “you want your readers to be able to talk about your book”!

Don’t use too similar names for different characters (unless it serves a plot purpose). You don’t want your reader to mix them up and get confused.

In real life, people do have unusual names. And there isn’t always a (big) story behind it. But when characters in your story have unusual names (whether the protagonist, the antagonist or a secondary character), readers assume there is a reason (and it better be a good one), that you did it on purpose. Unusual names stand out, so if you give a character an unusual name, you better know why.

Once you’ve come up with a name, check the Internet. You don’t want your protagonist to unintentionally share the name of a criminal, a person well known in another English-speaking country, or an important character from someone else’s books. (Don’t use names that are too similar to well-known characters either.)

Oh, one last tip: Don’t name your protagonist after your kid – or your kid after your protagonist!