Before Brittany became part of France in the 16th century (see my post here), it was an independent duchy. The Breton language, a Celtic language related to Welsh, Cornish and Cumbric, was used there for many centuries, since before the year 1,000. It evolved from Old Breton over Middle Breton to today’s Modern Breton. The number of speakers fell dramatically in the mid-20th century due to the national policy of recognizing only French as official language in the 19th and 20th centuries.

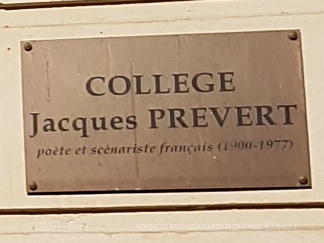

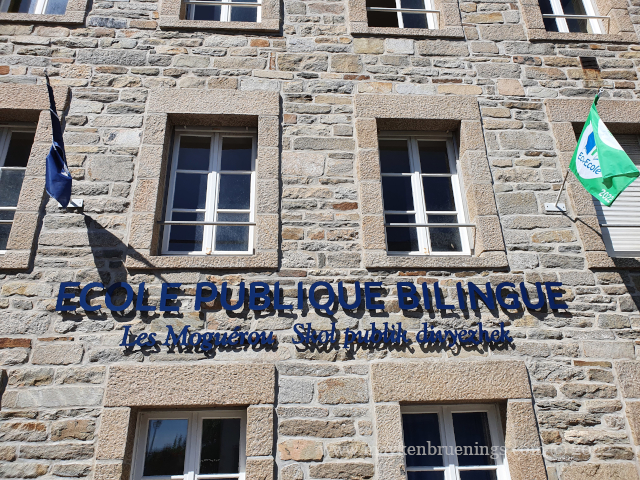

Today, however, the Breton language is part of the regional Breton movement, and there are not only over 50 Breton-speaking schools (Diwan schools) but also numerous private Catholic and public schools with Breton classes.

The Diwan school association estimates the number of Breton speakers at 400,000. (Brittany has around 3,3 million inhabitants.) However, many Breton speakers are elderly people, and few actually use it in everyday life.

Five times so far, France has chosen to be represented at the Eurovision Song Contest with songs in regional languages, twice of those in Breton: in 1996 and in 2022. Numerous books and comics have been translated to Breton, local hero Asterix among them but also Belgian reporter Tintin, as well as the Peanuts.

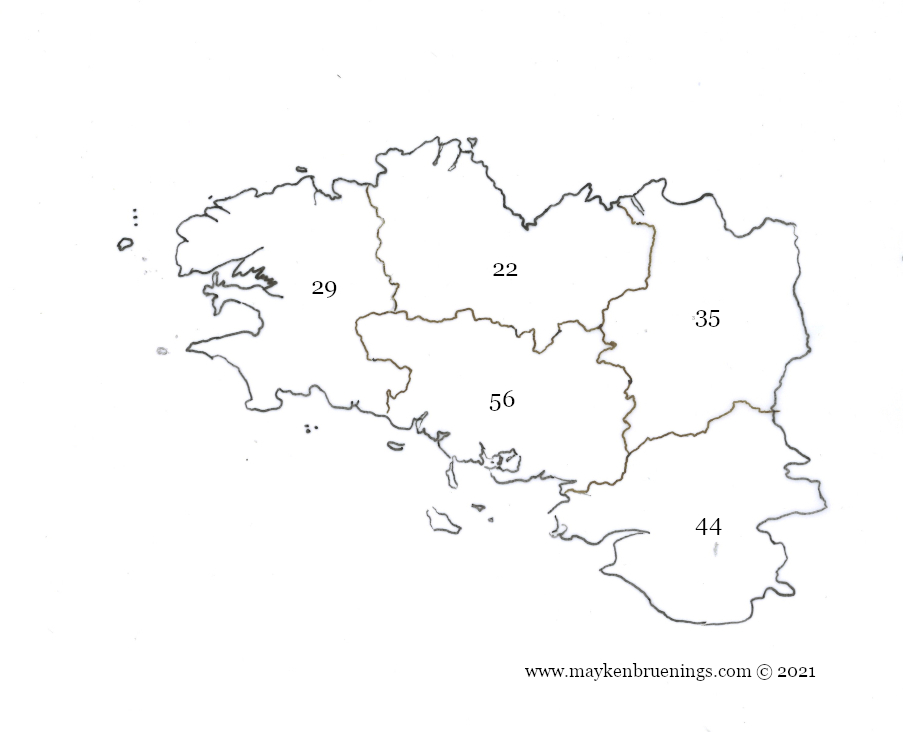

When you visit Brittany, you won’t see it much until you are about halfway into the region. That is where the bilingual signposts will start, and where municipalities will put up signs with “Welcome” and “Goodbye” (Kenavo). However, the deeper you advance into Brittany, and especially in the département Finistère, you will see pretty much all signage in both languages, whether street names, the tourist office, the train station, or “other directions” (da lec’h all).

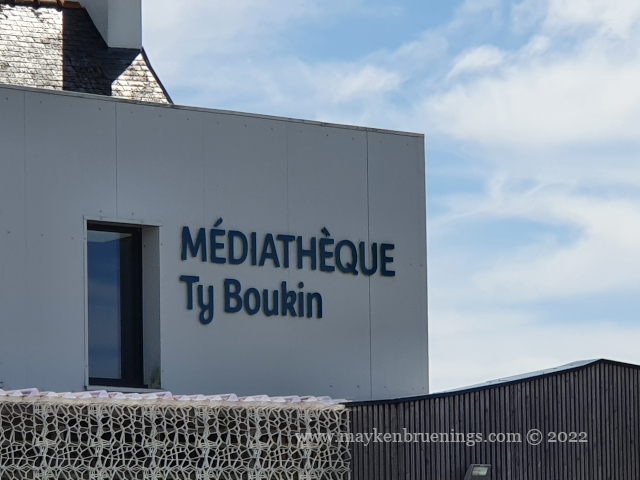

If you compare terms, you will be able to figure out some words. Ty, for example means house, and ker means town. So what might a ty ker be? A town hall, of course. My personal favorite is one I discovered this summer, a municipal library, or ty boukin.