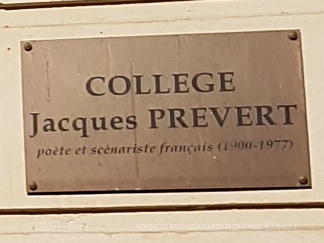

My first French manual in school had a lesson that started with this sentence:

En France, les enfants de onze à quinze ans vont au college.

Aside from the accumulation of nasals, this sentence contains more precious information about the French school system that hasn’t changed since I started learning French:

In France, the children from age eleven to fifteen go to collège.

The collège, then, is the rough equivalent of middle school. From grade 6 on, years are counted backwards, like a countdown to the baccalauréat:

Sixième (6e) – grade 6

Cinquième (5e) – grade 7

Quatrième (4e) – grade 8

Troisième (5e) – grade 9

The counting continues in the lycée, high school, for the final three years:

Seconde (2nde) – grade 10

Première (1ère) – grade 11

and finally, at the end of the countdown:

Terminale (terminal year) – grade 12

This is when French students pass their leaving exam, the baccalauréat I mentioned in part 1.

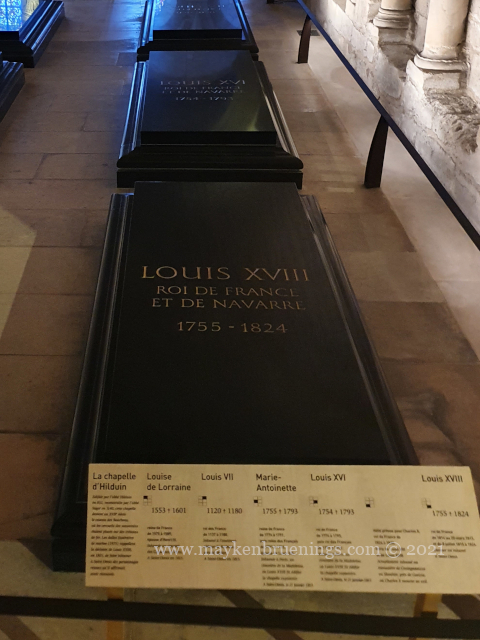

Speaking of part 1, do you remember I said school in France is secular? That’s right, just as there is a separation between Church and State, there is a separation between Church and School (which, after all, is run by the state). So unless you send your kids to a private religious school, thew will get a secular education.

This has led to a curious characteristic of the French school system: the Wednesday.

At first, I assume when school ran Mondays through Saturdays, there was no school on Thursdays, so that children could receive the religious education of their family’s choosing. In 1972, the day was moved to Wednesday.

Écoles maternelles and écoles primaires were closed on Wednesdays, and this could extend to Wednesday afternoons in collège. As a result, extracurricular activities are concentrated on Wednesdays too (now supplanting religious education), and parents who work at 80% frequently have their Wednesdays off.

A few years ago, however, the government decided to rebalance school hours and open schools on Wednesday mornings to allow for shorter afternoon classes on the other days. This resulted in many protests, as the responsibility for after-school daycare is the responsibility of municipalities, which were not necessarily of the same political color as the government.

In the end, the government backtracked and allowed each département to choose whether to open schools on Wednesday mornings or not. Welcome to France.