You have never seen it. You haven’t queued for tickets, and you haven’t been inside to see the Mona Lisa. I know you haven’t because le château du Louvre is not what you think it is. It is not the giant palace in the center of Paris housing one of the most famous museums in the world. That would be the Louvre Palace, le palais du Louvre.

Nit-picking, you say? Tell that to King Philippe-Auguste (reign: 1180-1223) who had the château du Louvre (the Louvre Castle) built to reinforce the wall he had built around the city.

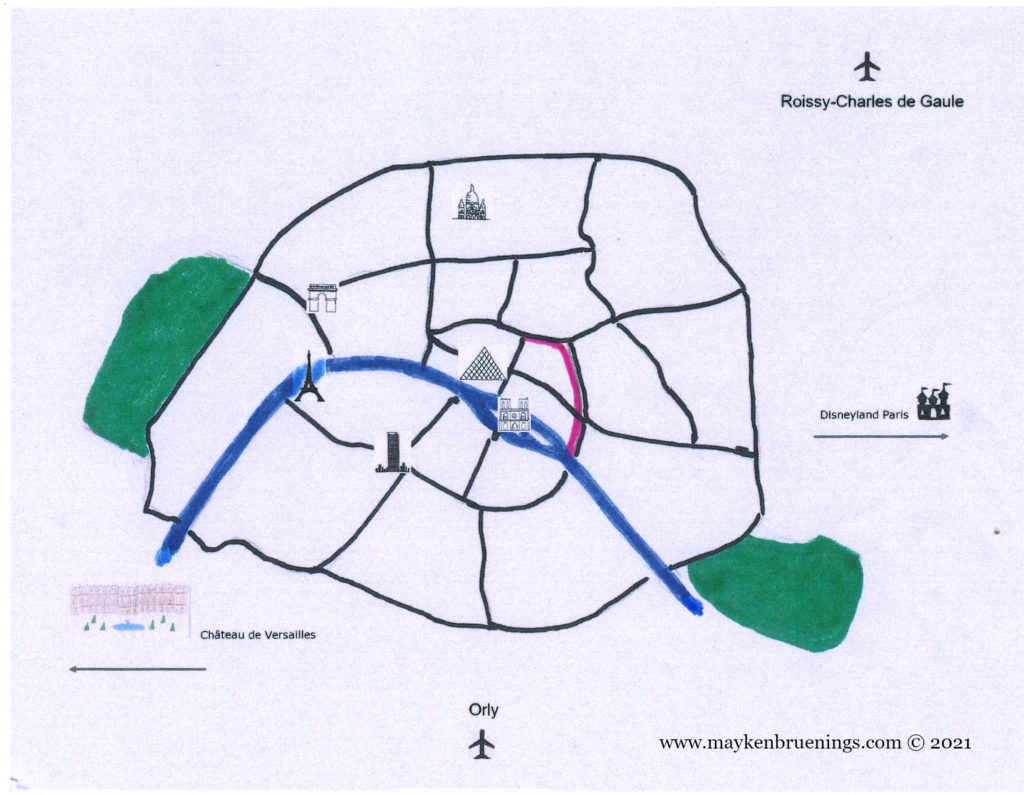

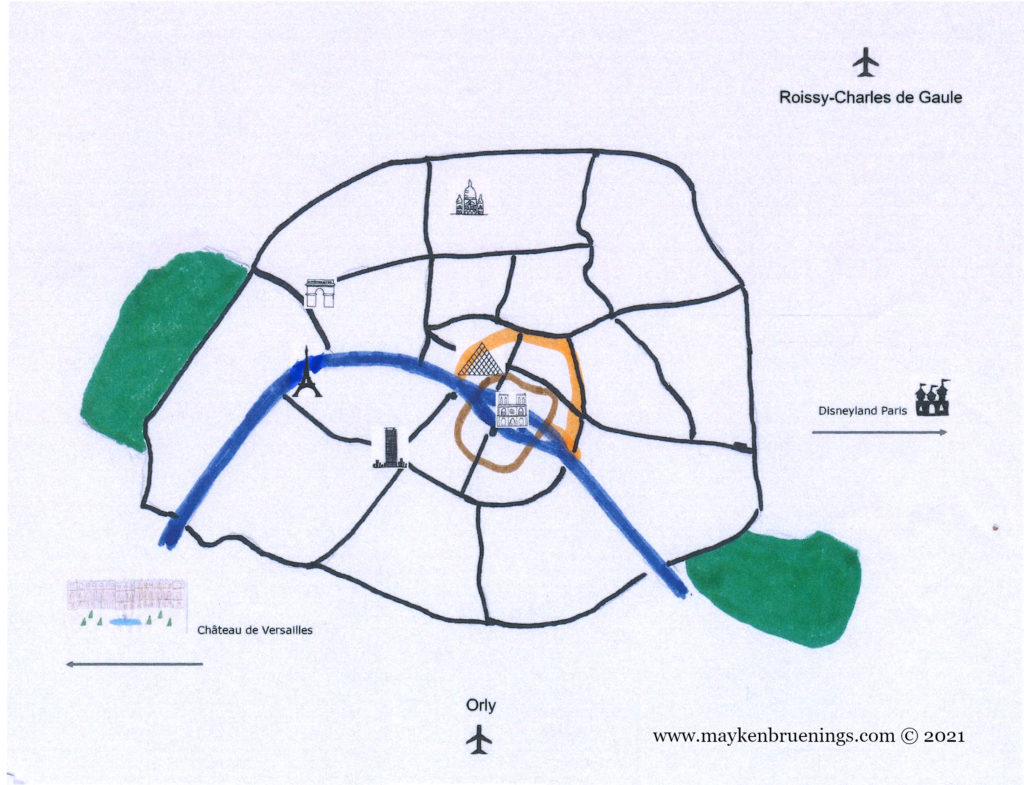

The château du Louvre was built near the river at the western end of the city, where the risk of an attack was highest as the English occupied Normandy less than 100km away. Philippe Auguste also wanted a safe place for his treasure and for his archives which had been lost in a battle with Richard Lionheart but since been reconstituted. The château du Louvre was roughly square with a moat surrounding it and a round keep at the center.

At the time of King Charles V (reign: 1364-1380), Paris had spread past the old city wall, and Charles V had a new wall built. The château du Louvre lost most of its military significance, and the king could sacrifice some of the protective building aspects to make it more habitable while still providing a safe place for the king, notably after the revolt of 1358 led by the Prévôt des Marchands Étienne Marcel.

During the Hundred Years War, the English under King Henry V were allied with the Burgundians who held Paris, so the English could enter the city and occupied the château du Louvre without a fight. They stayed from 1420 to 1436.

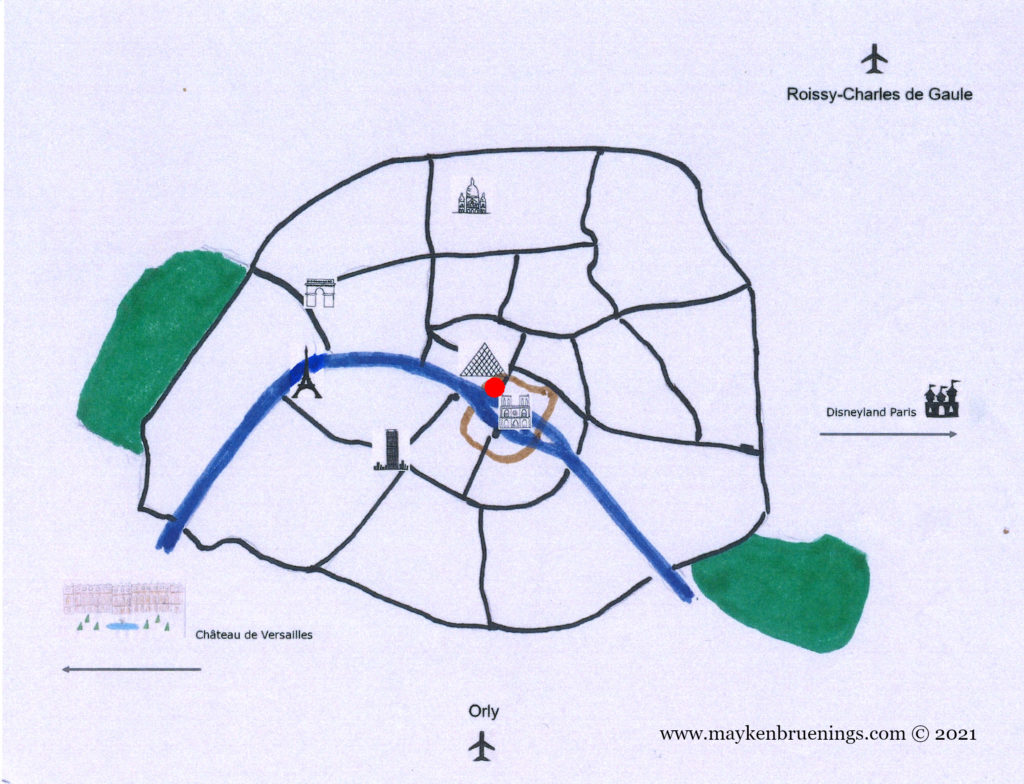

Successive French kings demolished the château little by little and built new structures on top. During works in the 19th century, it was discovered that the foundations of the château du Louvre hadn’t been destroyed completely. The basis of the keep and two walls were cleared during the works for President François Mitterrand’s Grand Louvre project, and can be seen today during a visit of the Palais du Louvre’s famous museum, the Musée du Louvre.