If you come to Paris at a certain time of the year, or stay for a while and use public transport on a regular basis, you might come across some animals.

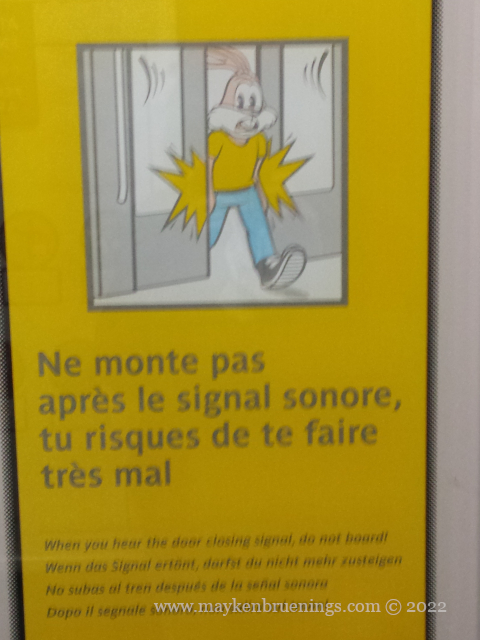

First up: Serge le lapin, the official Paris metro bunny and quite probably the stupidest and/or unluckiest bunny in France.

Serge has been around for 45 years, getting his paws stuck in the sliding metro doors. I’ve also spotted him getting hurt on the escalator.

So far so good, but what are the chameleon and the beaver doing on Paris transport? I’ll let you make a guess first, just for fun.

I’m sure you didn’t get it, it’s very far-fetched.

Caméléon (chameleon) and castor (beaver) are the names of two different replacement services. Caméléon busses jump into action when one of the RATP’s ten tram lines is interrupted for one hour or more.

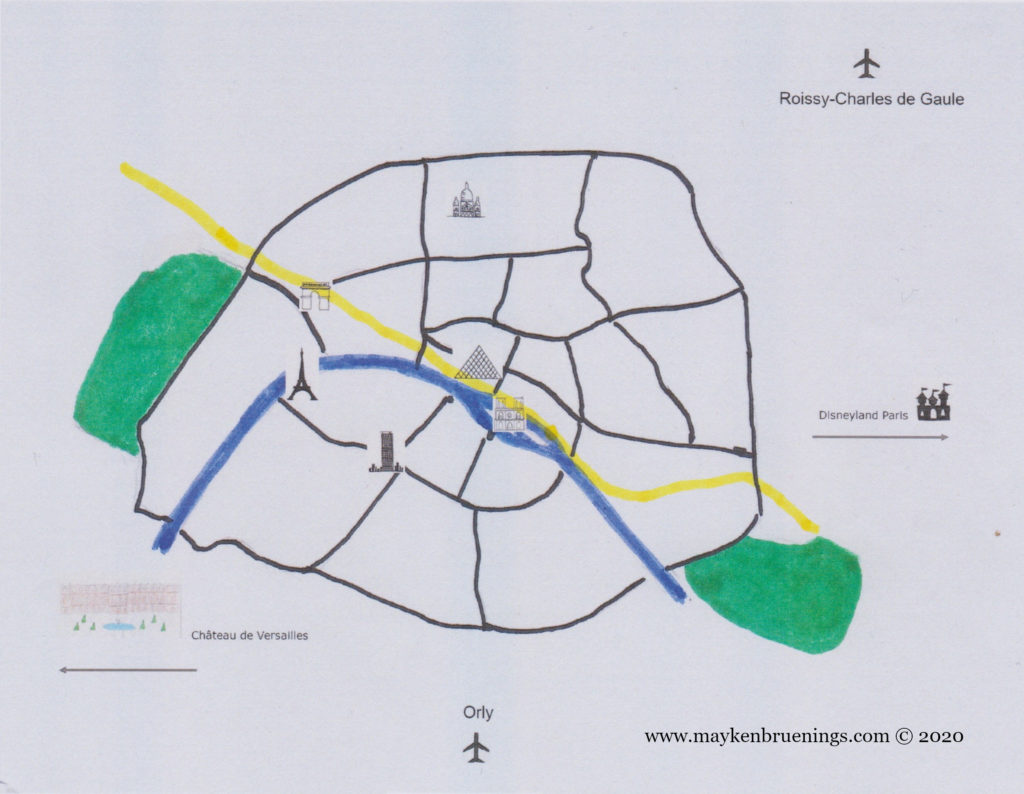

Castor (beaver) is the name of the replacement bus service for the central Paris section of the RER C train that runs along the Seine river through aging tunnels . The almost two decade long “Beaver works” project takes place every summer when the section is closed down entirely for a month or longer, and the “beaver buses” take over. Since this is high tourist season, and the closed section of the RER train includes Notre Dame, Musée d’Orsay, Invalides and the Eiffel Tower, it might actually be useful to know.