The Statue of Liberty was created by the French sculptor Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi, with the metal framework built by Gustave Eiffel. It was a gift of the French people to the United States of America and was inaugurated on October 28, 1886.

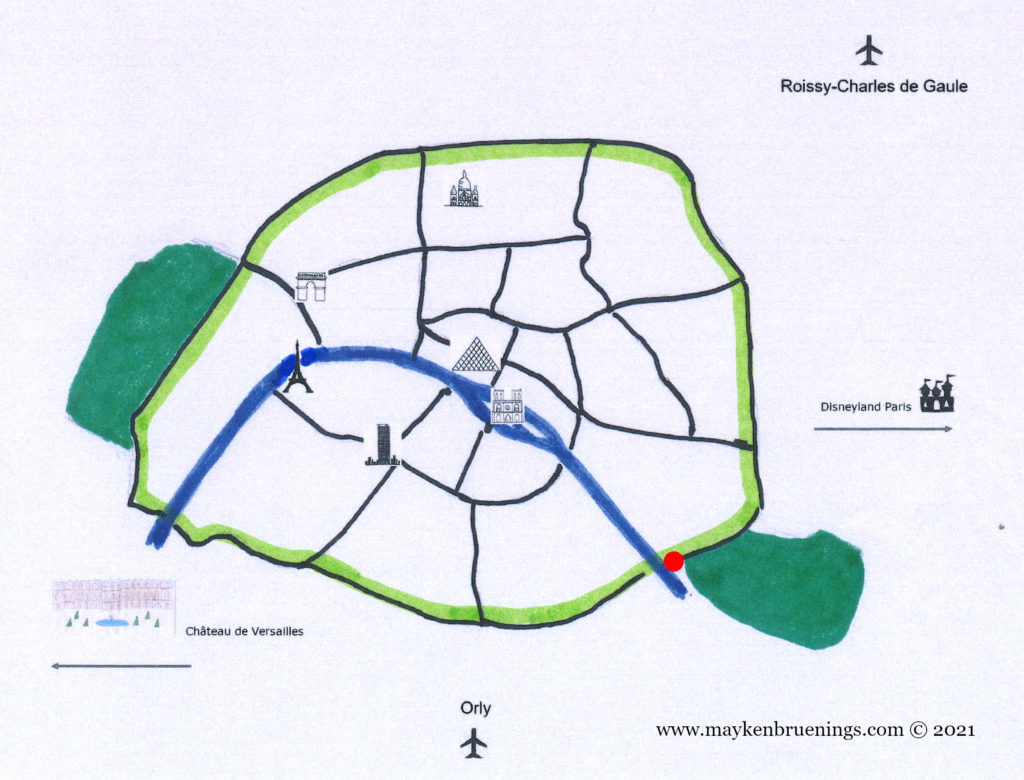

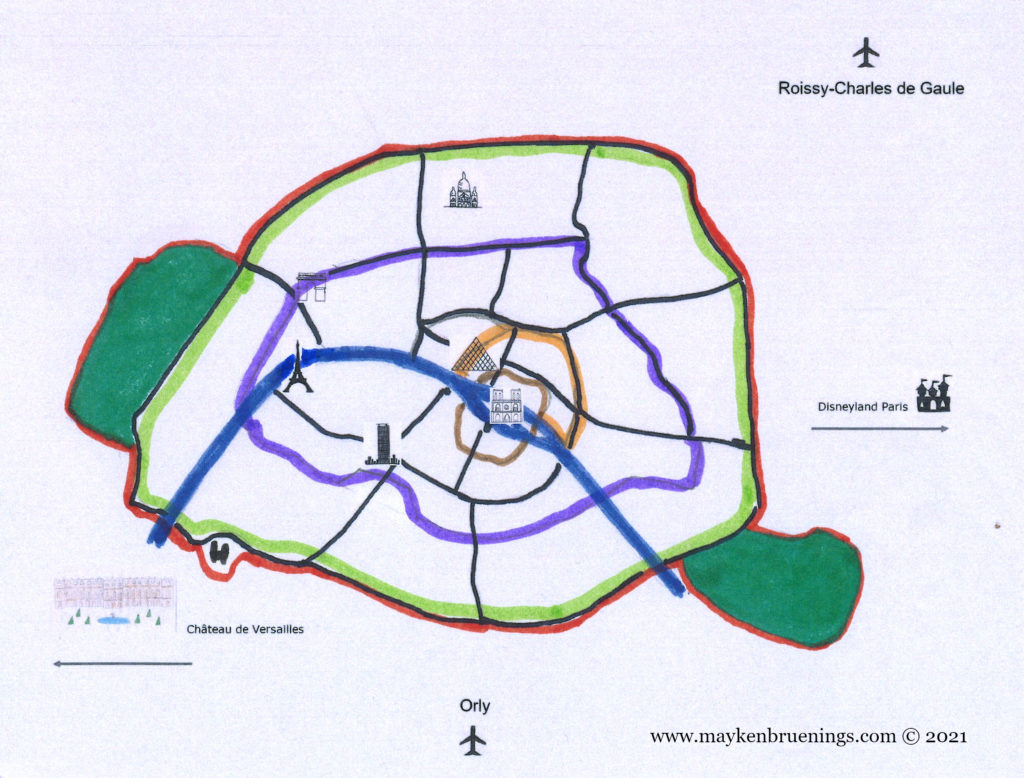

Bartholdi first created a reduced-size model in plaster which you can now find a the Musée des Arts et Métiers in Paris. In the courtyard of the museum, there is a bronze made from this plaster made by the museum.

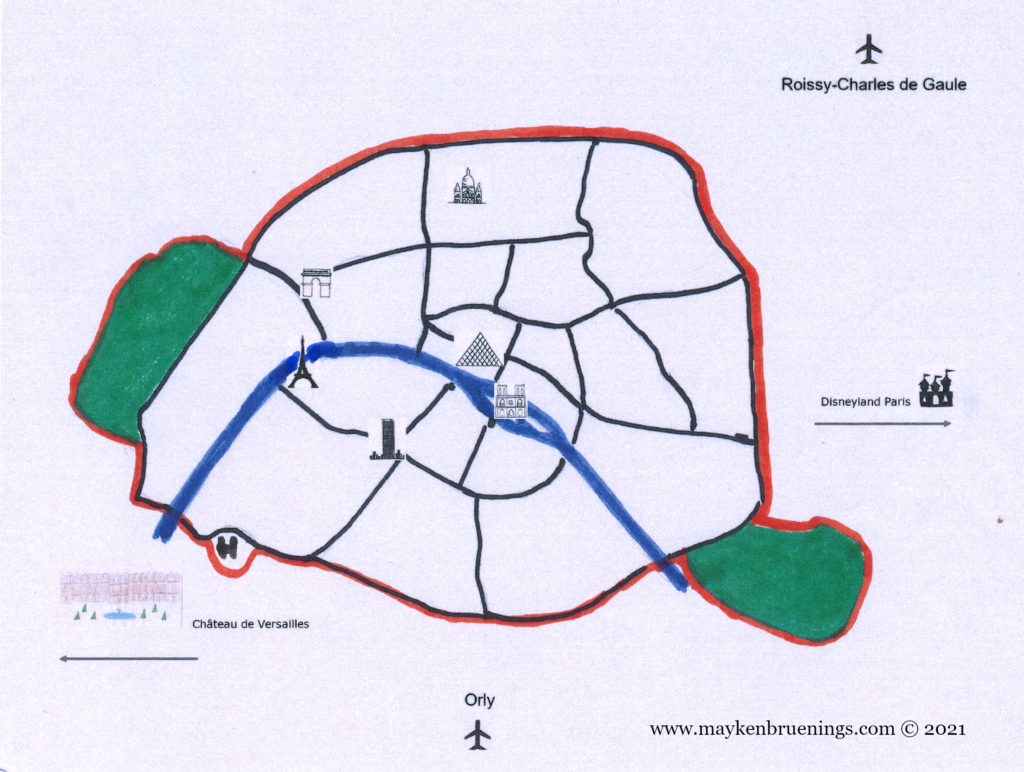

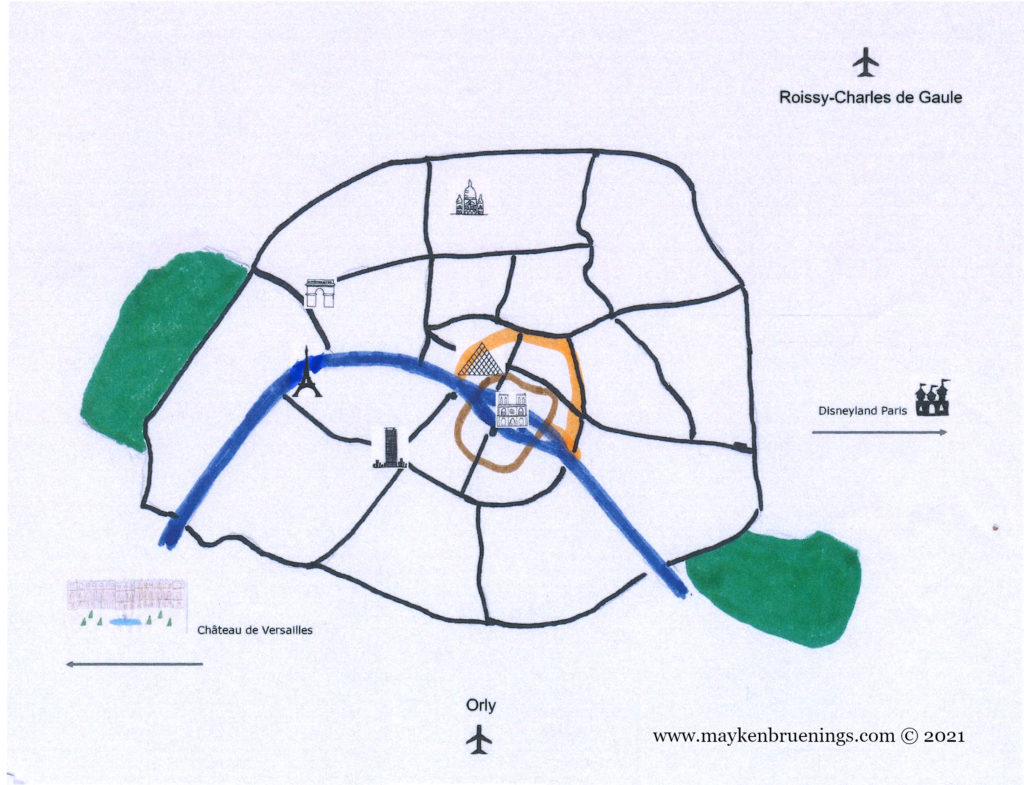

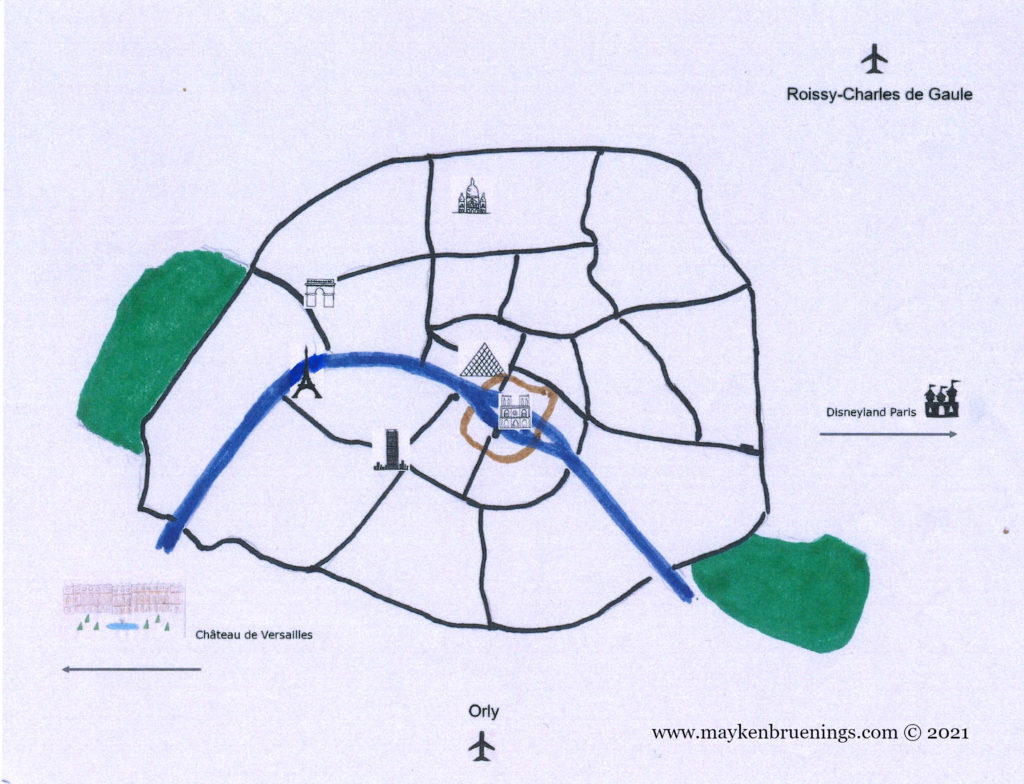

The first bronze model made from the plaster was given by Bartholdi to the Musée du Luxembourg in 1900. The statue was set up in the Luxemburg Gardens but in 2012, it was transferred to the Musée d’Orsay and replaced in the park by a copy.

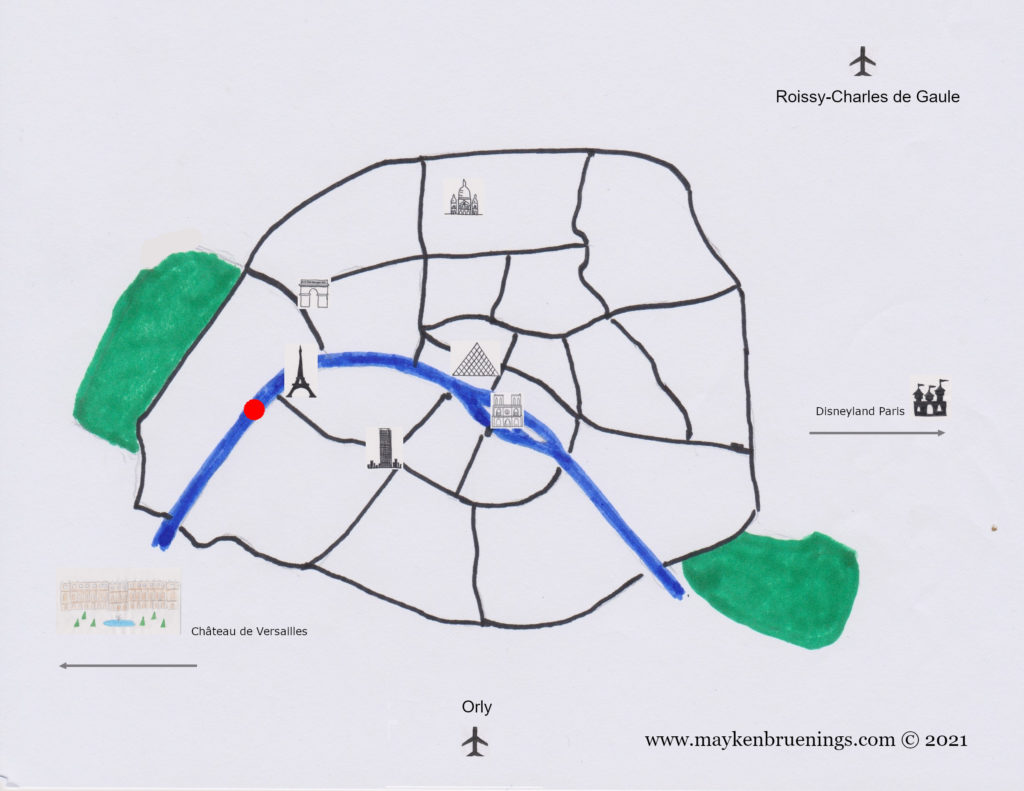

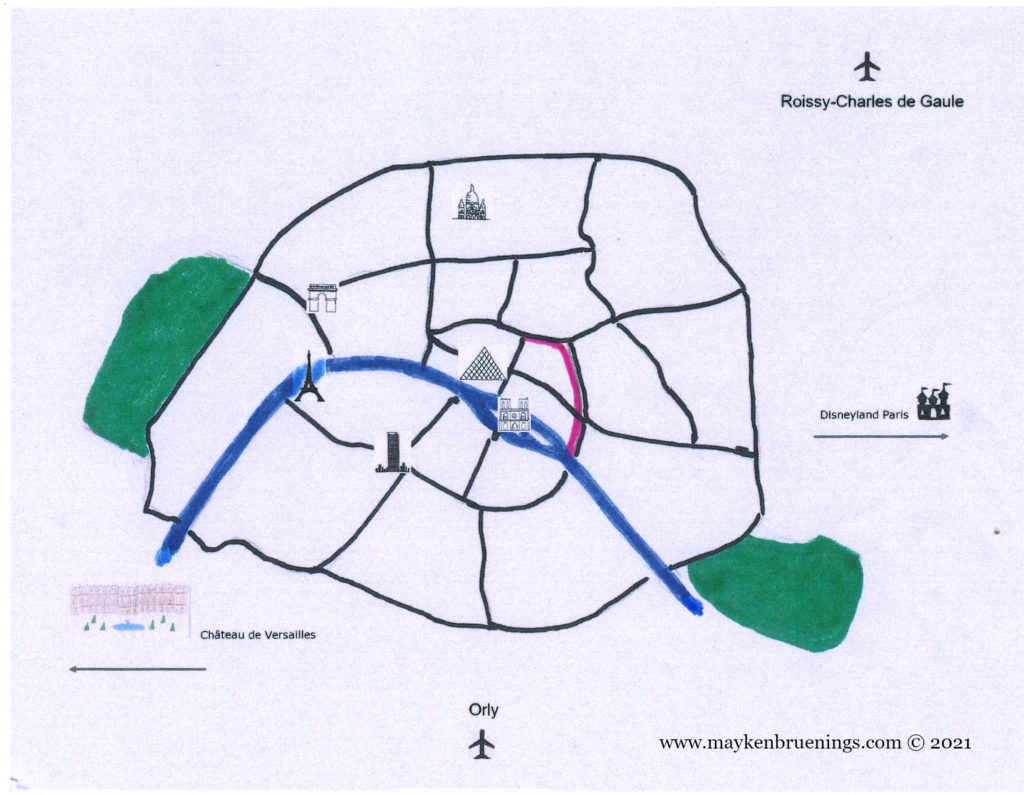

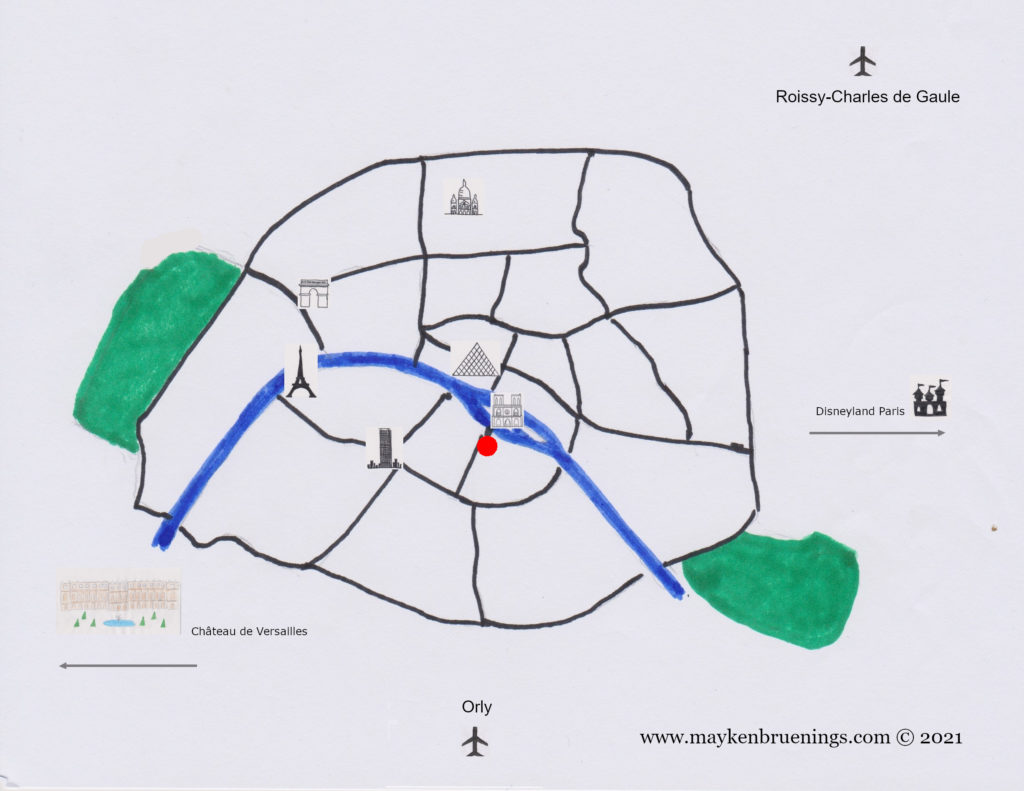

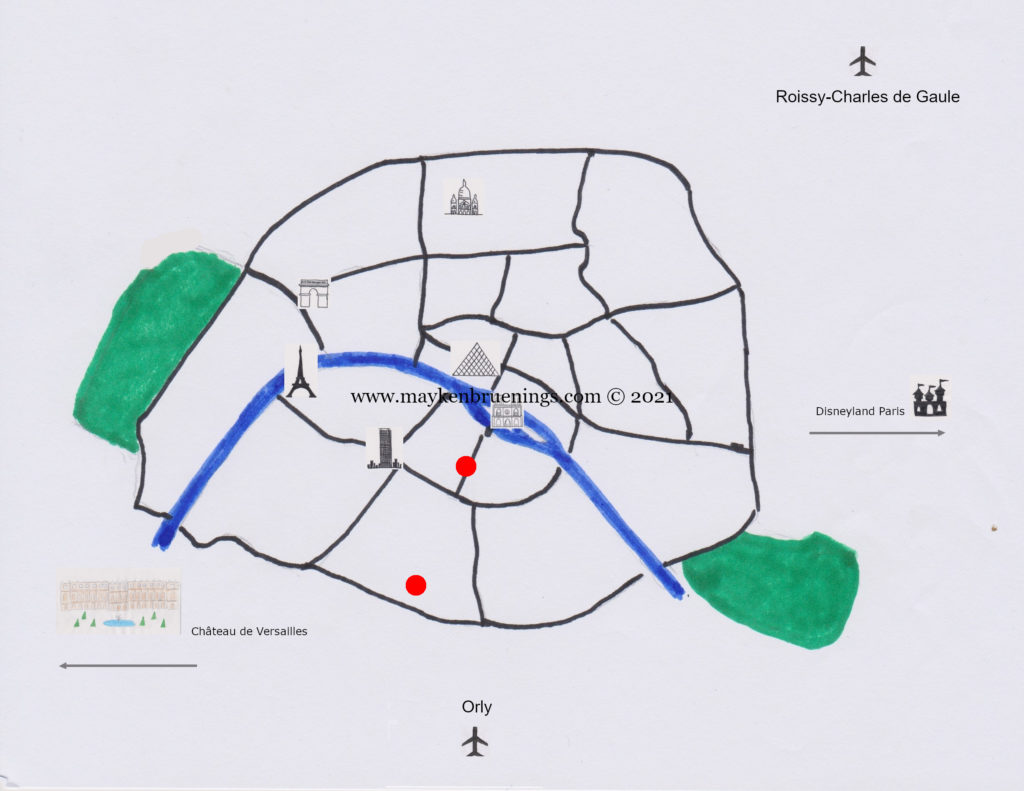

In 1885, another bronze copy was made and given to France by the Committee of Americans in Paris at the centennial of the Revolution. It was set onto the Île aux Cygnes (an artificial island in the Seine that was created to support, among others, the Pont de Grenelle bridge) at the height of the Pont de Grenelle, near the place where Bartholdi’s workshop was.

It was inaugurated by President Carnot on July 4, 1889, three years after the original statue in New York, and in the presence of its creator. The statue looked eastwards so that the president didn’t have to inaugurate it from a boat and to inaugurate a statue that turns its back on the Elysée (the presidential palace) despite Bartholdi having asked that it look towards New York. The statue was finally turned to look towards its big sister for the 1937 World Fair.

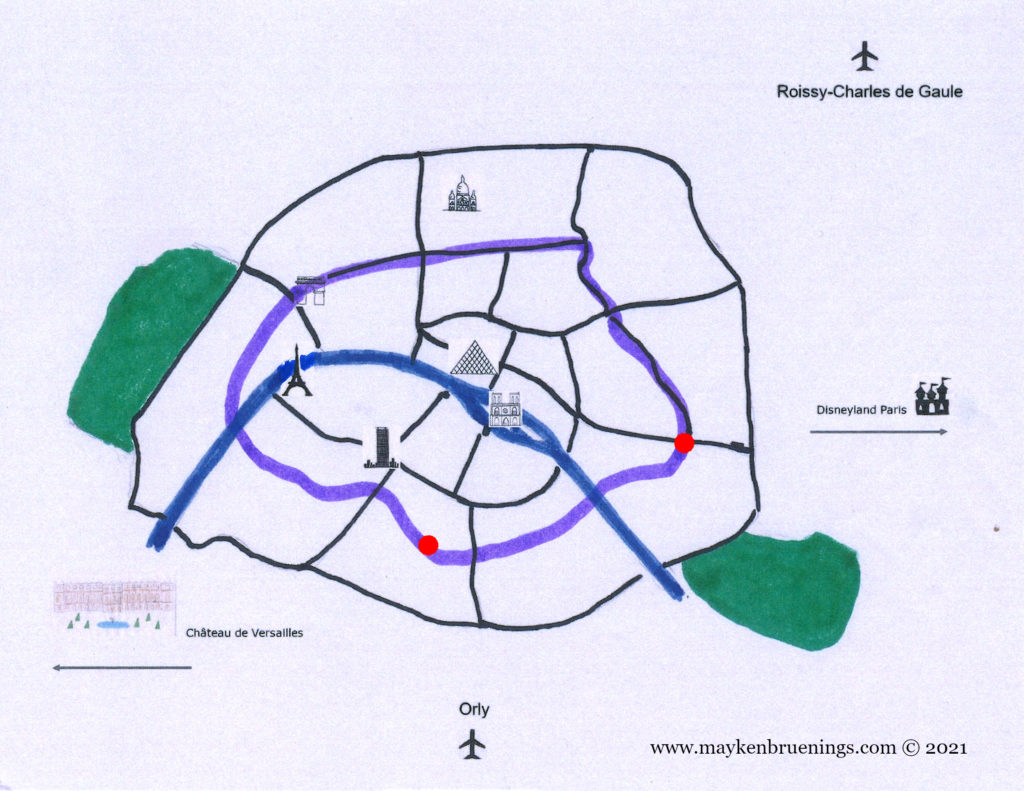

Since 1989, there is also a replica of the flame in its original size. It is located on the Place de l’Alma, a gift from the United States to the City of Paris. It is best known nowadays as the remembrance site from Princess Diana who died in 1997 ins car crash in the Tunnel de l’Alma just below the monument.