When you find yourself with an avalanche of human bones in your basement, you know it’s time for change.

Which is what the city of Paris did when exactly that happened to neighbors of the Cimetière des Innocents in 1774. Looking for a place to store the bones from the overflowing inner-city cemetery, they came up with the idea to put them in the decommissioned stone quarries underneath the city.

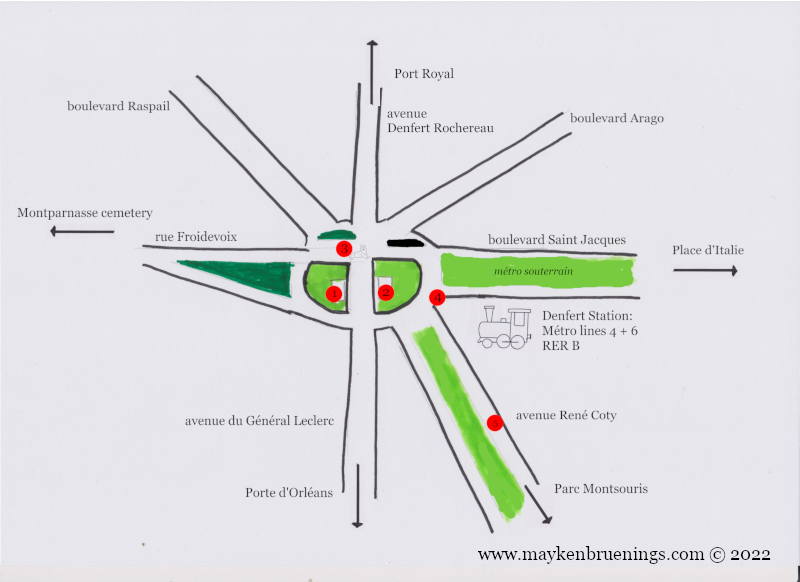

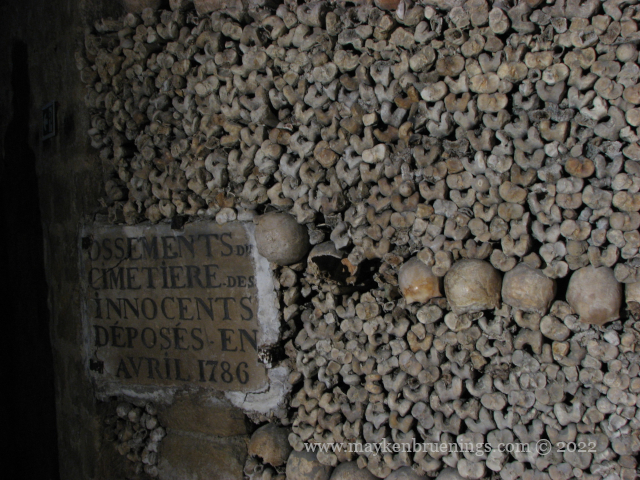

After arrangements had been made, bones from the various cemeteries of Paris, Les Innocents included, were carted to a chute in the avenue René Coty (near Place Denfert-Rochereau) to be stored underground. The name Catacombes was borrowed from Ancient Rome, even though there were no graves and funerary monuments. At first, the bones were stacked along the tunnels over hundreds of meters. It was only after the first VIP visits at the beginning of the 19th century that the bones were somewhat organized. More cemeteries had to be closed as the city grew, and their bones were added to the ones already in residence.

Signs were added to indicate the cemetery of origin, and the gravediggers arranged skulls and bones in patterns that can still be seen today.

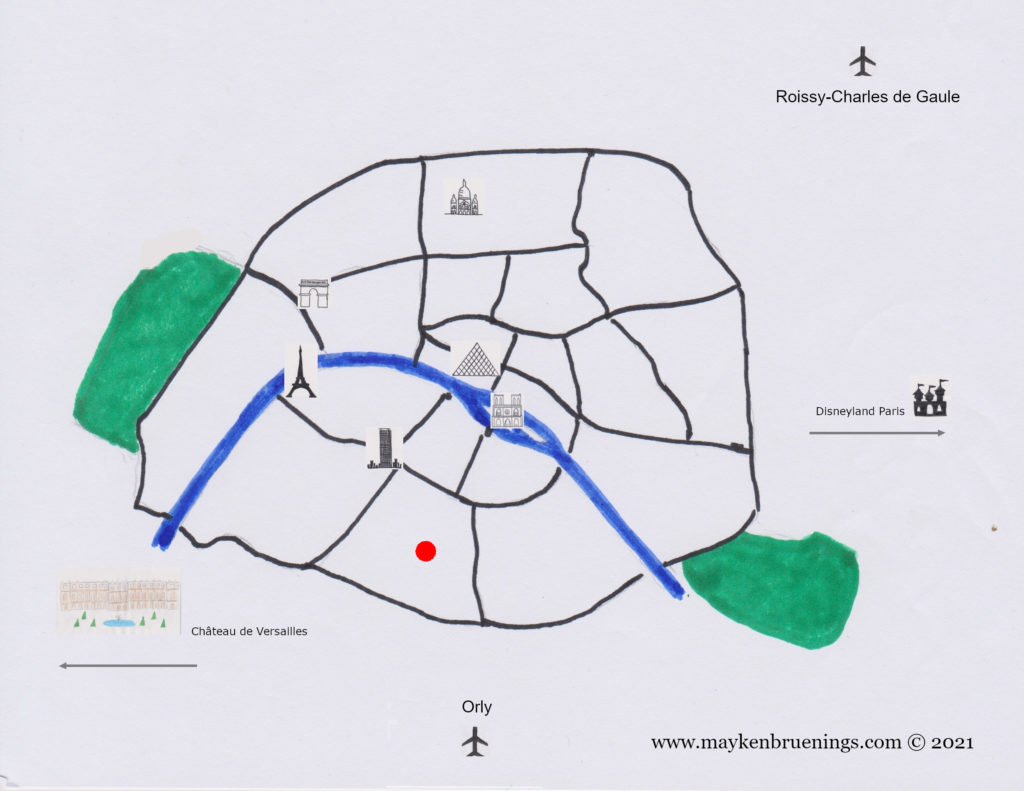

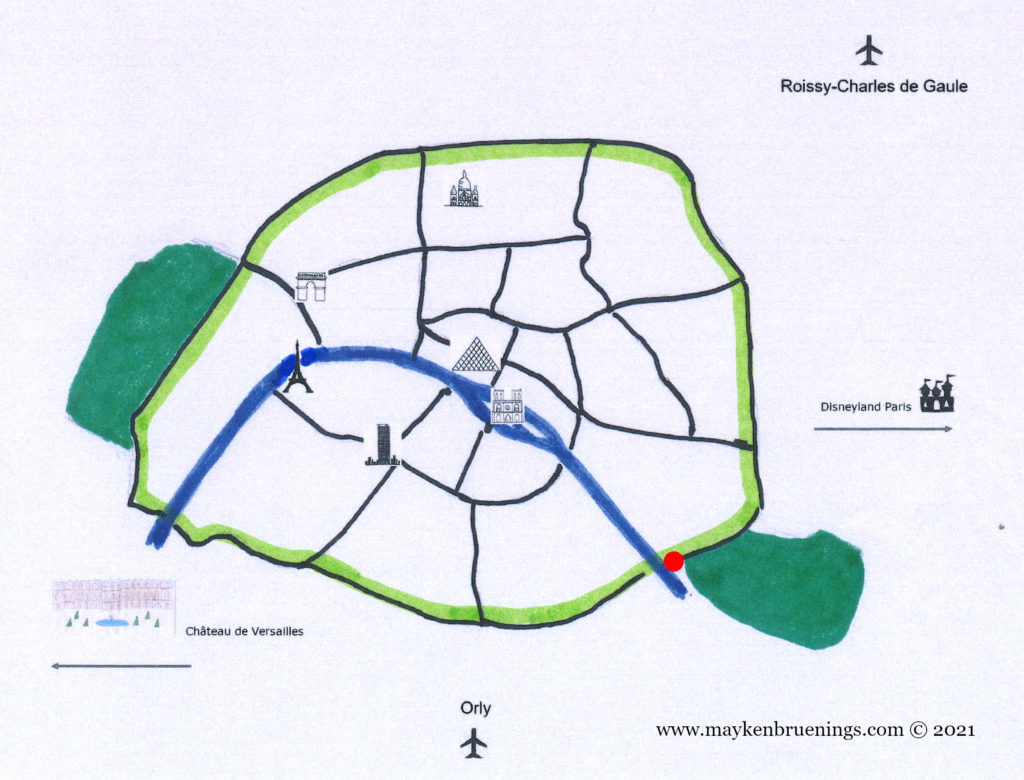

In 1809, the Catacombes became a museum that today is part of the Musée Carnavalet and gives visitors access to a small fraction of the tunnel network of Paris’ ancient stone quarries.

In one of the first sections of the visit, sculptures made by a quarryman in the late 18th century can be seen. They represent sites from Port-Mahon on the Spanish island of Minorca where he was said to have been a POW.

There used to be a long line of visitors starting out from the old entrance and winding back around the square behind the eastern lodge of the barriére d’Enfer (entry point of the General Farmers’ Tax Wall), but recently, it was closed in favor of a new entrance, and the ticket sale has shifted online, so now visitors can book their spot in advance and don’t need to queue any longer.

old entrance

new entrance

exit at 21 avenue René Coty