Brittany is the westernmost part of France, jutting out into the Atlantic ocean. It has over 1.100km of coastline, double that if you include the numerous islands.

Traditionally, you distinguish between the Armor or Arvor, the coastal or maritime area, and the Argoat, the interior.

The climate in Brittany is temperate, with more rain than the French average, but the southern coast and its beaches get less rain and more sunshine than the Monts d’Arrée mountains in the interior. (Mountains being a big word, as they culminate at 385m.)

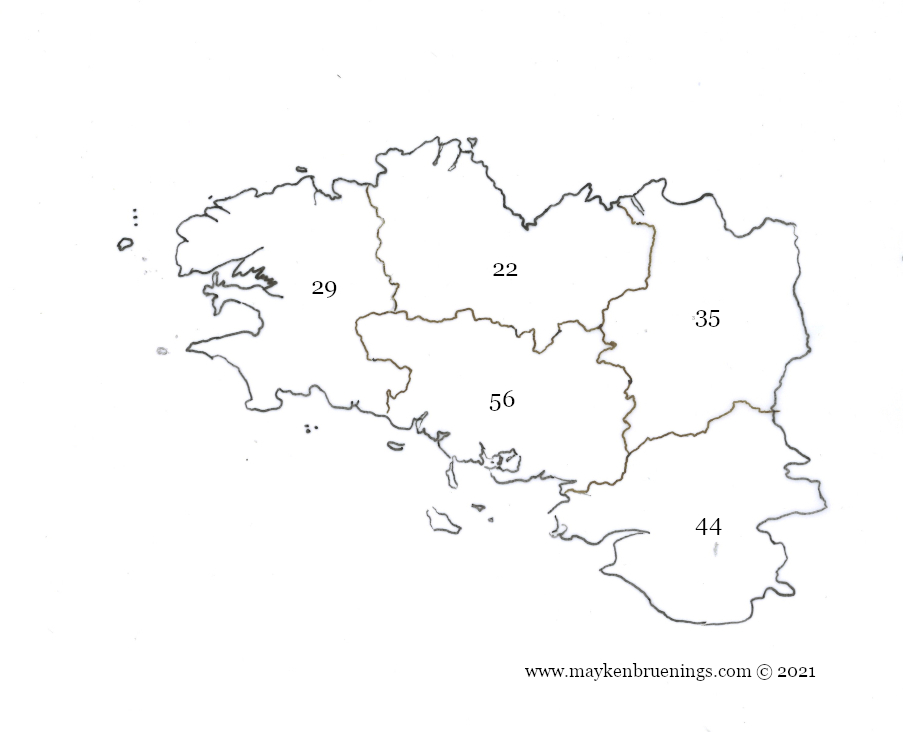

The administrative region Brittany is divided into four départements: Ille-et-Vilaine (35) in the east, with the regional capital Rennes; Cotes d’Armor (22) in the north, Finistère (29) in the west, and Morbihan (56) in the south.

Historically, the département Loire-Atlantique (44) with its main city of Nantes, also belongs to Brittany. Actually, Nantes was the seat of the Duke of Brittany, the château des ducs de Bretagne is still there to prove it.

Fun facts:

The numbers behind the département names correspond to their numbers in French nomenclature, which includes the first two numbers of the postal code and the number on the right side of the license plate, above the regional logo. Many Bretons living in the Loire-Atlantique replace the Pays-de-la-Loire regional logo with a sticker of the Brittany logo (the Gwenn ha Du).

The Morbihan is the only French département (of which there are 94 in mainland France (not counting Corsica and the overseas ones) whose name is not in French. Morbihan means “little sea” in Breton and refers to the Golfe du Morbihan.

Brittany was annexed to France in the 16th century. King Charles VII married Anne de Bretagne who brought her Duchy into the marriage. In order to make sure Brittany was attached to France no matter what, the wedding contract included a clause that if Charles died without a heir, Anne would have to marry his successor.

Which is exactly what happened – Charles VII died an untimely accidental death (he hit his head against a door frame despite being only 1,52m tall) and Anne married his successor Louis XII. They didn’t have any male children either. Louis’ successor François Ier married the daughter of Louis and Anne, Claude, who inherited the Duchy of Brittany from her mother but who couldn’t inherit the throne of France from her father.

Long story short: François and Claude had several sons, and in 1532 Brittany became officially part of France.