From its completion in 1875 until 1989, the Paris opera house on the Avenue de l’Opéra in the 9th arrondissement was simply known as “Opéra de Paris”. But with the completion of the Opéra Bastille on Place de la Bastille arose the need to distinguish between the two, and so the old opera house is now referred to by the name of its architect, the Opéra Garnier.

A failed assassination attempt on emperor Napoléon III when he visited the then-opera Le Peletier with his wife in January 1858 accelerated the project of a new opera house.

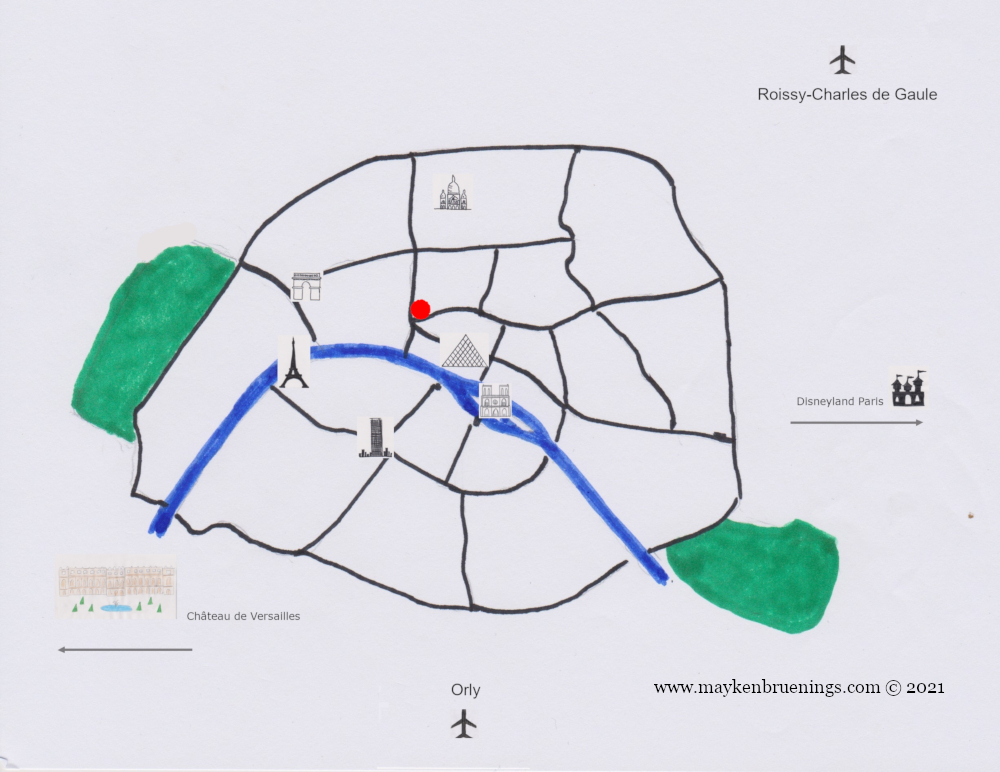

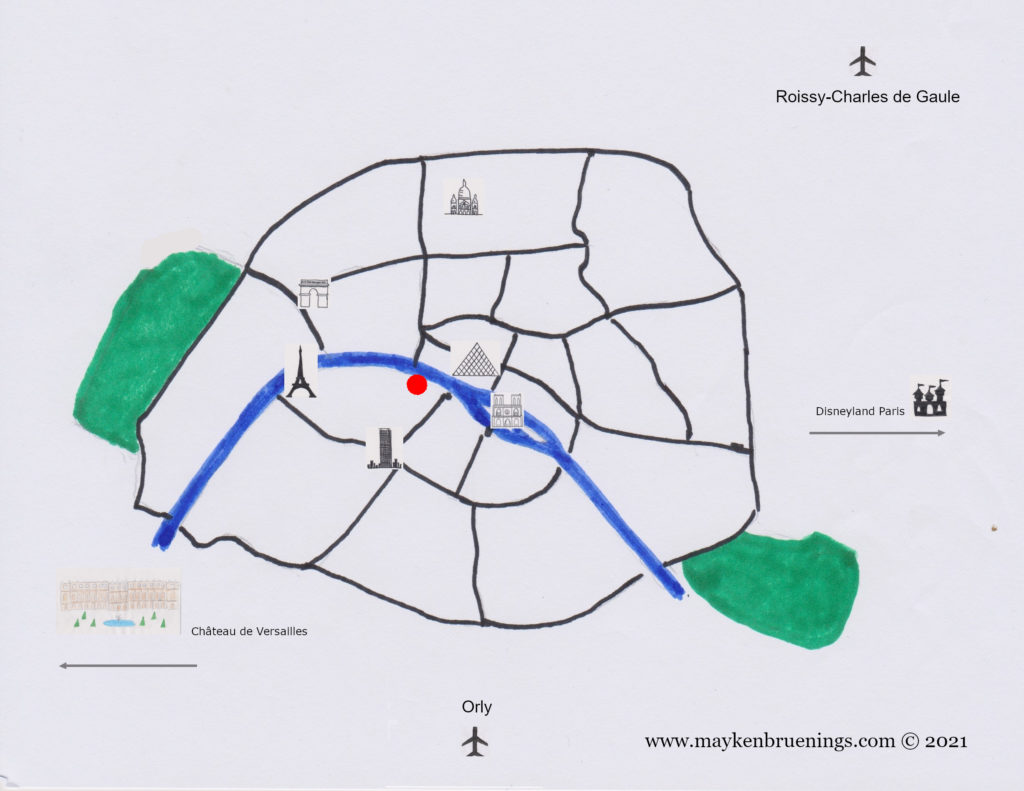

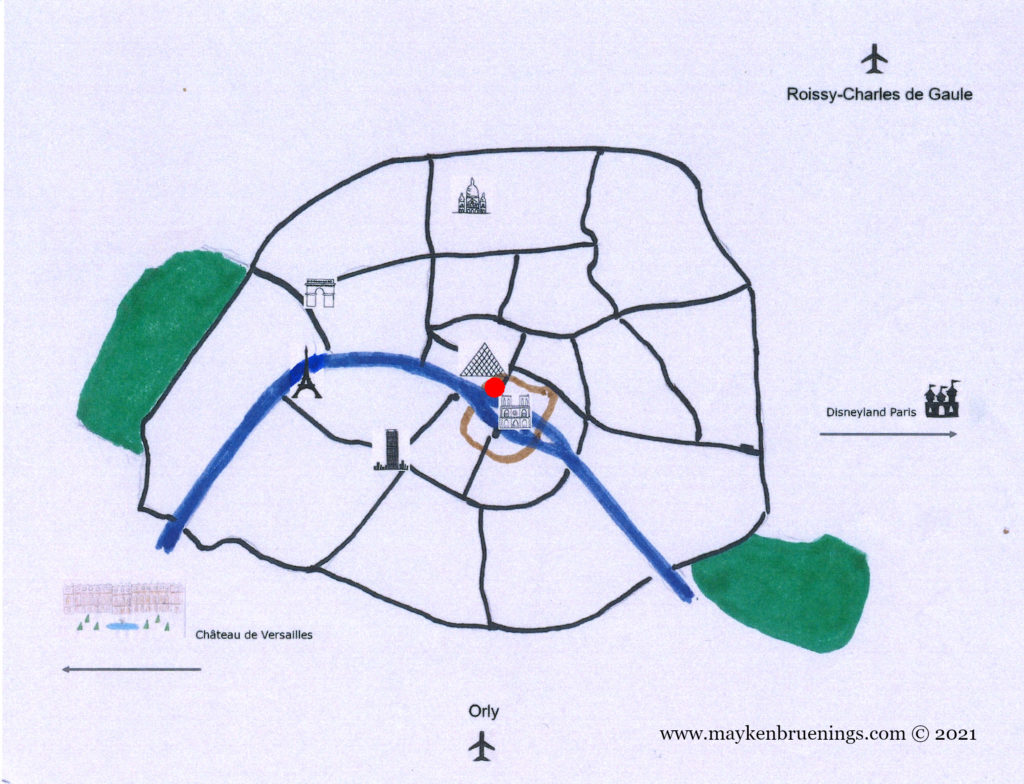

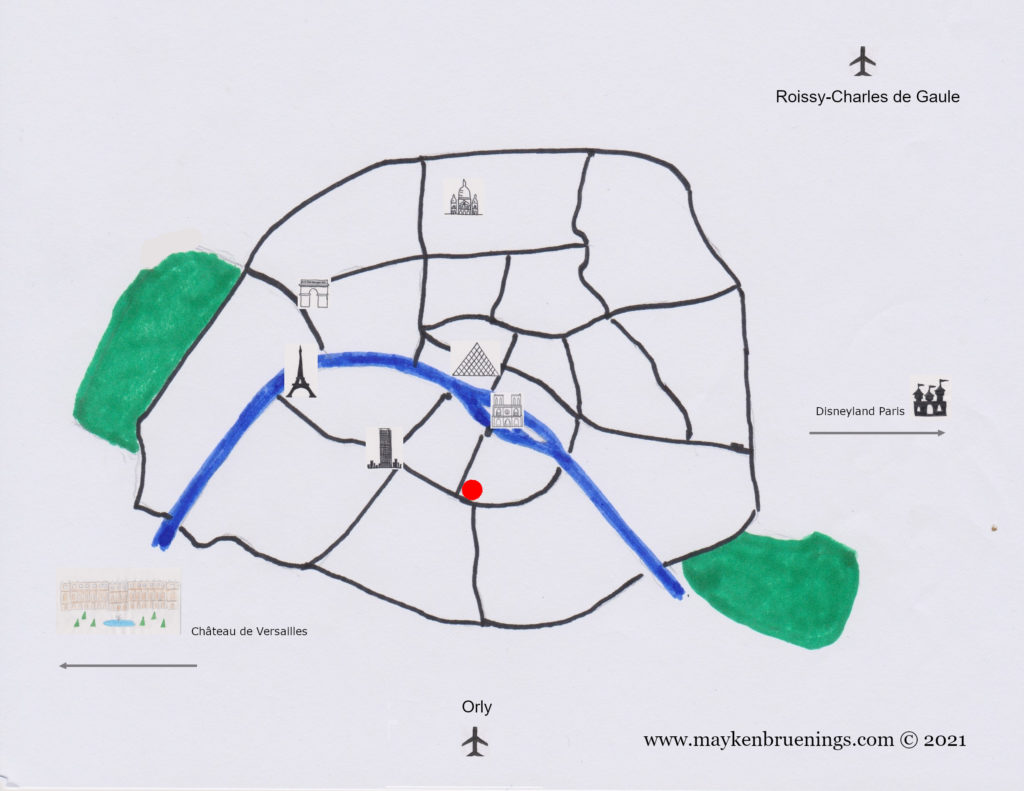

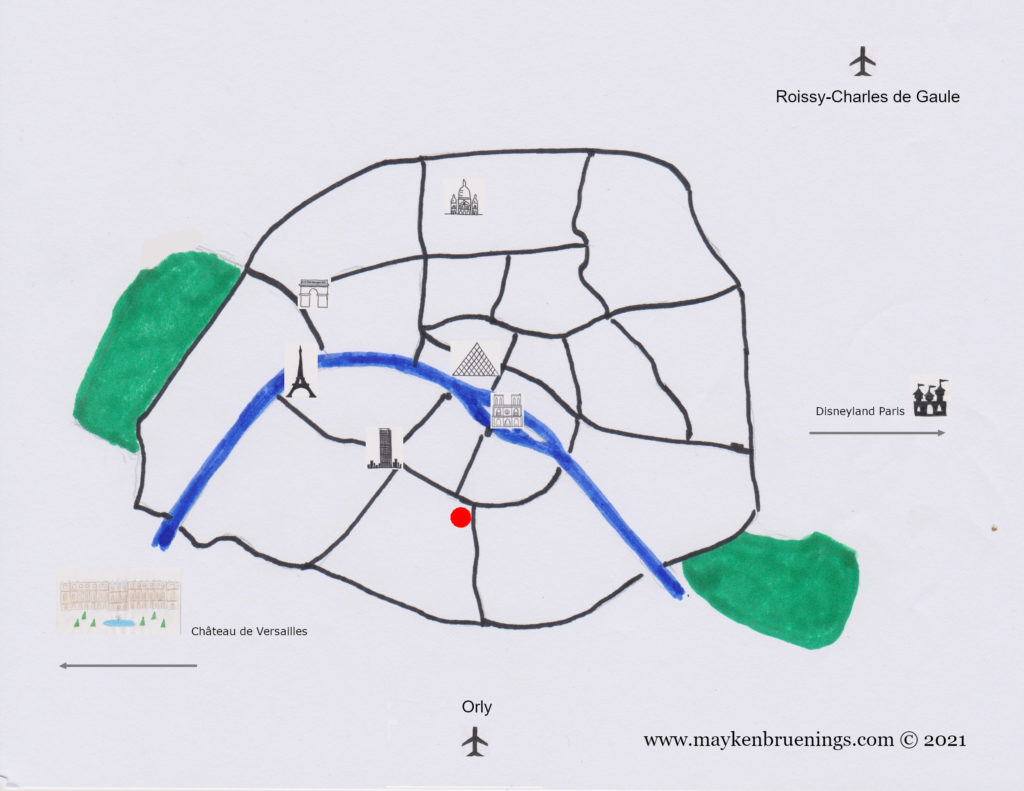

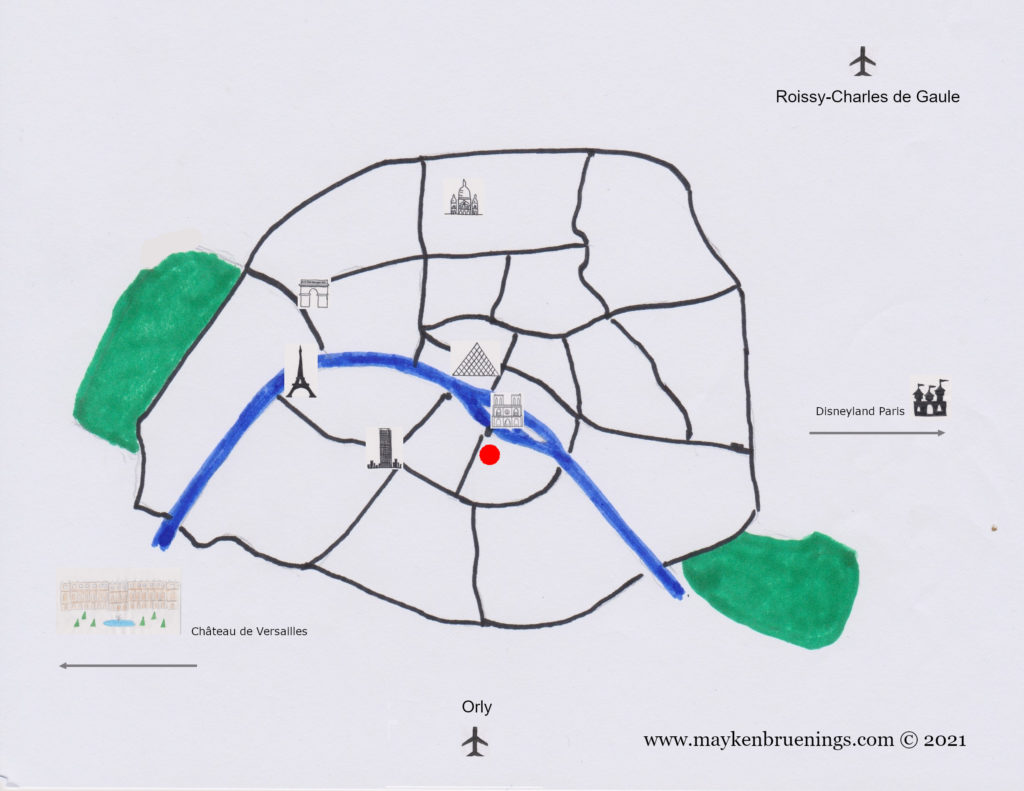

The site was chosen by Baron Haussmann who planned it to surround it with the characteristic Immeubles de Rapport (Revenue Houses) that you’ll remember from a previous post.

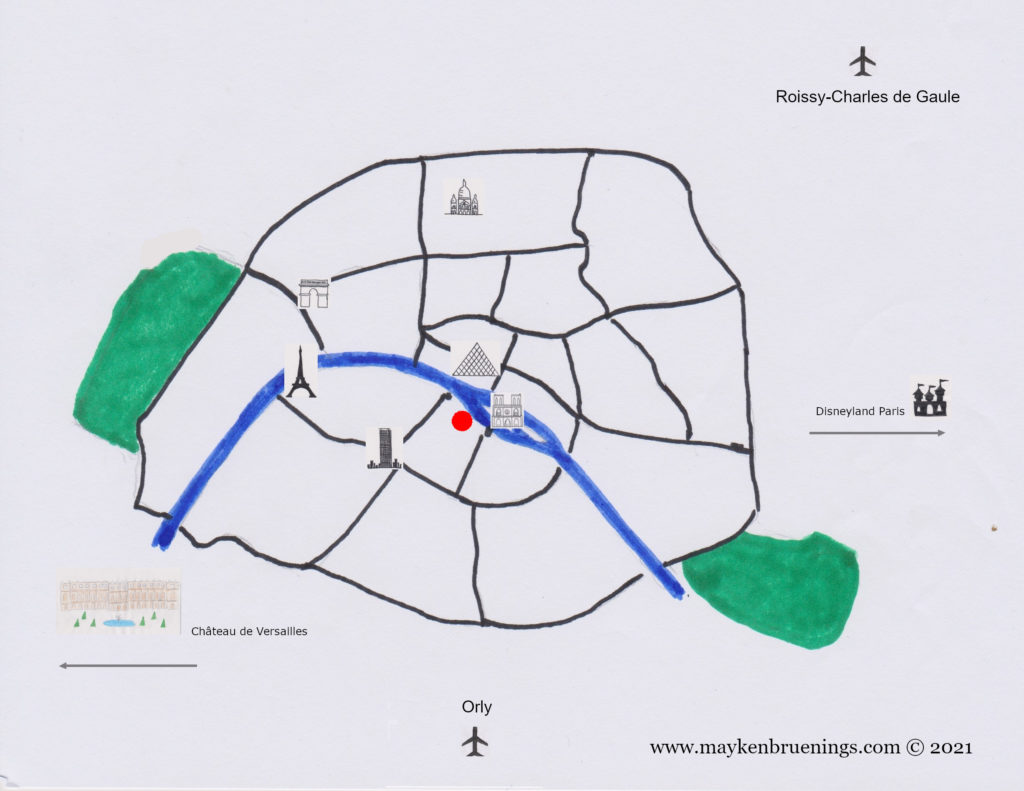

The large Avenue de l’Opéra Haussmann planned would not only create a vast perspective and showcase the new opera house, it would also allow for a swift and unencumbered escape route for the emperor from the opera to the Louvre in the event of another attack.

Still today, the Avenue de l’Opéra has no trees so as not to obstruct the view.

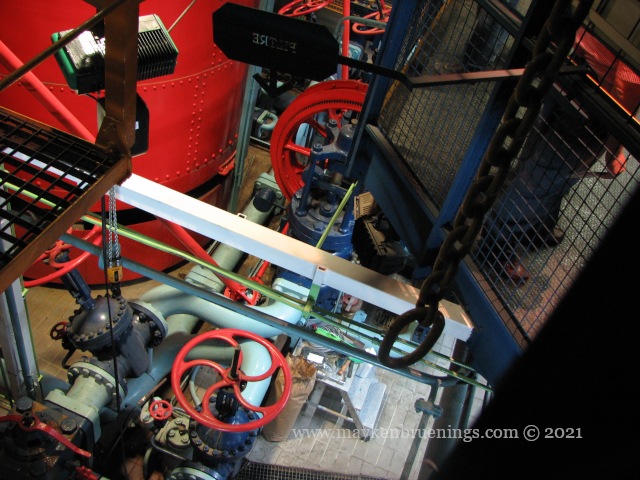

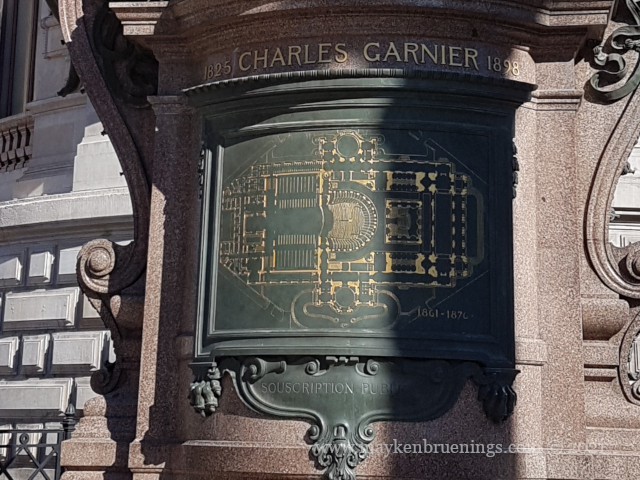

The chosen site however turned out to be far from ideal to accommodate a palatial building such as the opera house. Despite sinking wells and having pumps operate non-stop, the groundwater level wouldn’t go down. In the end, Garnier designed a double foundation including an enormous cistern.

At the occasion of the World Fair in 1867, still under Napoléon III, the main façade was inaugurated. An anecdote from this inauguration goes like this. The empress, shocked at the sight of the opera building, asks “What kind of style is that? That’s no style! It’s neither Greek, nor Louis XV, not even Louis XVI!” The architect, Garnier replies: “No, the time of those styles are over. This is Napoléon III style!”

The Franco-Prussian War of 1870/71 not only slowed down the works but it also brought about the end of the Second Empire. The Third Republic that followed had financial difficulties and didn’t approve of everything the opera symbolized, and sent Garnier packing, but when the Le Peletier opera burned in 1873, he was called back to finish the works.

Poor Garnier – once the opera was finally completed in 1875, the Third Republic, cutting ties with the past, didn’t even invite him to the inauguration and he had to buy his own ticket!

Until 1989 and the Opéra Bastille, the Opéra Garnier was the biggest theater house in the world. Today, it mainly shows ballet by the Ballet de l’Opéra de Paris but also the occasional classic opera.