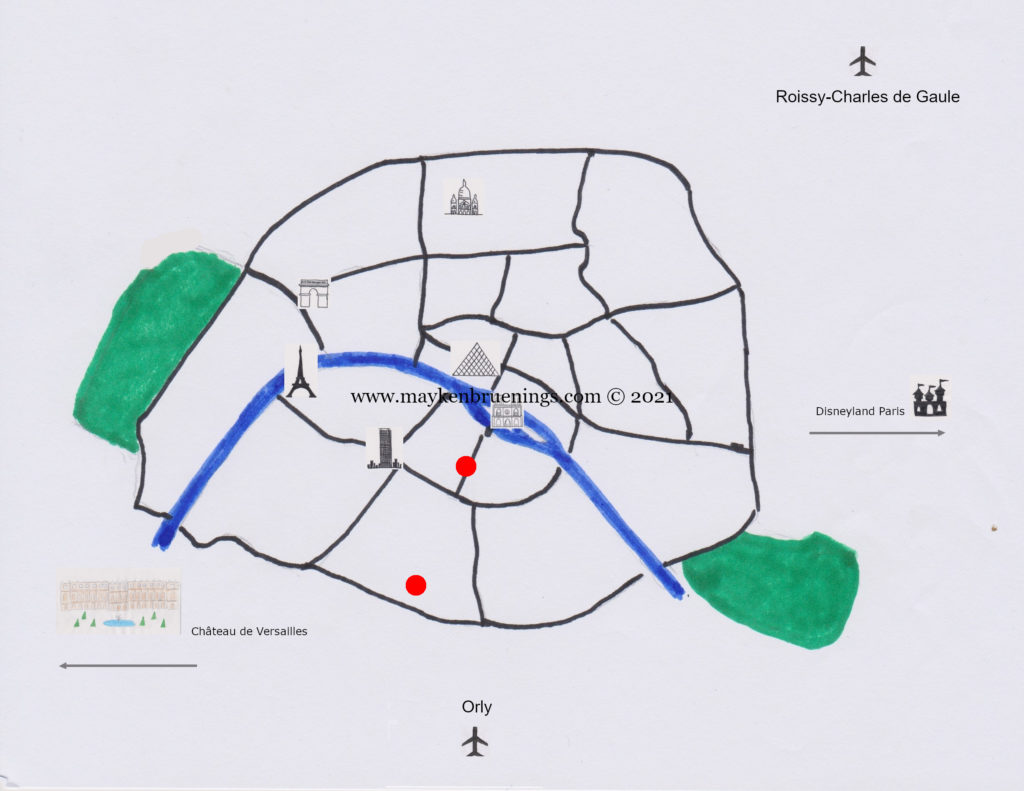

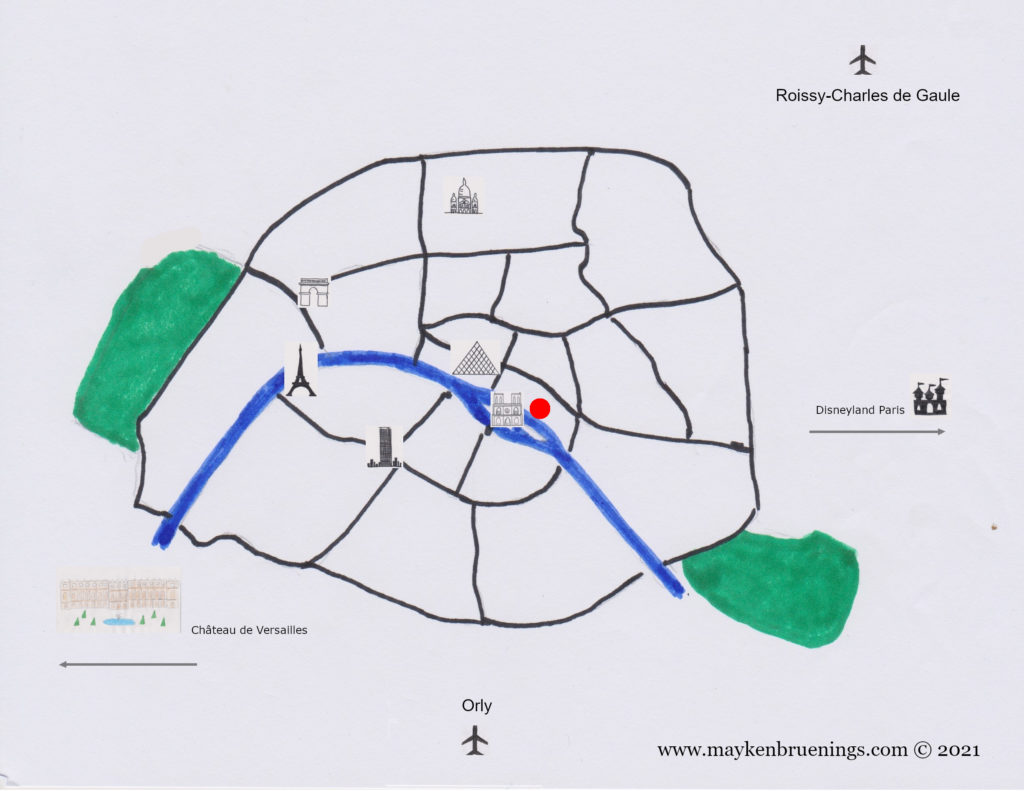

The Montparnasse office tower is the highest building inside the Paris city limits, and for 40 years it was the highest building in France. The tower was built on the site of the old Montparnasse train station. The new Montparnasse station is just behind it, with long-distance trains going to the entire Atlantic coast up to and including Brittany, and commuter trains to the suburbs and Versailles.

The tower is 209m high, with a rooftop terrace on the 59th floor and a restaurant on the 56th, both open to the public for a magnificent view of Paris. The elevator, fastest in the world at the time of construction, only needs 38 seconds to reach the top.

The other floors are mainly occupied by businesses, with 5,000 people working in the tower on a daily basis.

In recent years, major asbestos removal works have been undertaken, as the tower was built during a period when the danger of asbestos was not recognized.

But what is one lonely skyscraper doing in the 15th arrondissement?

The tower was subject to controversy before, during and after its construction (1969-1973). In 1975, the city of Paris decided to ban the construction of buildings higher than 7 floors, effectively cutting short any prospects of creating a skyscraper business district within the city limits. But by then, the construction of skyscrapers in the new business district La Défense on the western outskirts was already well under way.